Insights from Health Geographies II:

More-than-Human Healthscapes –

Tracing Animal and Environmental

Health and Care in Mainz

(summer term 2025)

Text and photos by Alyssia Özbeyaz

Cities are in many ways infrastructures of care and control, not only for humans, but also for animals, plants, microbes, and a variety of environments. Hence, more-than-human geographies can offer new insights and perspectives on health in urban landscapes. Embedding those health concerns and questions of co-existence and co-dependence of humans and more-than-human entities in the larger framework of “One Health”, “Eco Health”, “Public Health” and more broadly the post-humanist turn in the field of (health) geography can help tracing and understanding local healthscapes. The aim of this limited research project is the exploration of healthscapes in Mainz, particularly, how urban design makes more-than-human health visible, what it reveals about the interconnections between animal, environmental, and human well-being and how those infrastructures of care and control mediate the perception and health condition of more-than-human entities.

I

N

T

R

O

D

U

C

T

I

O

N

by Mara Linden

In summer term 2025, students enrolled in the MA programme Human Geography: Globalisation, Media, and Culture (MA) participated in the seminar Current Debates on Globalisation, Media & Culture: Geographies of Health, led by me (Mara Linden).

Throughout the seminar, we worked with different geographical perspectives within the field of health geographies, focusing on inequalities and power imbalances around issues concerning health in local and global contexts. We covered topics such as (post)colonial global health, health and environment, One Health and more-than-human health, before our focus moved to bodies, reproductive health, clinical labour and organ markets. From there, we continued to discuss the economisation of health and the focus on security and preparedness in much of global health.

The following blog post is one of several in a series of what we call “insights” from health geographies. These blog posts are the students’ works: They creatively engaged with the themes and perspectives taken up in the seminar and used their own empirical data – from interviews and observations to visual material – to write essays, create websites or produce films or podcasts. Through these works, the students expanded the seminar discussions, reflecting and adding to what health geography means. By making these works available online, we hope to open further discussions on health geographies’ entanglements with everyday experiences, social inequalities, and urban life.

More-than-Human Healthscapes: Tracing Animal and Environmental Health and Care in Mainz

by Alyssia Özbeyaz

Cities are in many ways infrastructures of care and control, not only for humans, but also for animals, plants, microbes, and a variety of environments. Hence, more-than-human geographies can offer new insights and perspectives on health in urban landscapes. Embedding those health concerns and questions of co-existence and co-dependence of humans and more-than-human entities in the larger framework of “One Health”, “Eco Health”, “Public Health” and more broadly the post-humanist turn in the field of (health) geography can help tracing and understanding local healthscapes. The aim of this limited research project is the exploration of healthscapes in Mainz, particularly, how urban design makes more-than-human health visible, what it reveals about the interconnections between animal, environmental, and human well-being and how those infrastructures of care and control mediate the perception and health condition of more-than-human entities.

_______________________________________

_

Theoretical framework: Post-human turn, more-than-human geographies and One Health

As seen in many other (sub-)disciplines as well, the post-human turn in geography has led to a widened scope of spatial dimensions of health, both challenging anthropocentric approaches and simultaneously acknowledging the deep entanglements of human, animal and environmental health. As Andrews (2018) highlights, those new, critical perspectives offer valuable insights into assemblages of human and more-than-human entities without disregarding the human element completely (Andrews, 2018, p. 1111, 1113). In this regard, the recognition of the living environment that makes human life possible is essential for geographical analysis of anthropogenic activity (Whatmore, 2006, p. 321). Alongside this post-human turn, the subfield of more-than-human geography has developed and gained relevance since the 1990s (Srinivasan, 2013, 107). Closely related to this, Foucault’s concept of biopolitics has been rethought through an ecological and multinaturalist lens, emphasizing how more-than-human agents are entangled with human activities – at times posing a threat to human life and health, while also being threatened by anthropogenic modes of urban and environmental governance at other times (Lorimer, 2012, p. 595, 598).

Those developments also correlate with approaches of the critical public health field, aiming to overcome the often very narrow association between public and human health and encouraging to consider other constituents, such as animals, plants, microbes, and built environments, beside humans as well (Rock, Degeling, Blue, 2013, p. 2). Companion animals are an example that illustrates that very notion quite well. While growing pet populations can increase risks of zoonotic infections, they can also promote physical activity (e.g. dog walking) and positively impact mental health through human-animal bonds and strengthened social interactions (Rock, Degeling, Blue, 2013, p. 3). These perspectives also draw from relational theories, such as the actor-network-theory, which emphasize the boundness and material relation between human and more-than-human agents (Rock, Degeling, Blue, 2013, p. 5). Donna Haraway similarly insists that human life is constituted through multispecies encounters and entanglements, which she frames as assemblages (Lorimer, 2012, p. 595; Rock, Degeling, Blue, 2013, p. 7).

Building on these perspectives, several conceptual frameworks have emerged throughout the last decades that center the linkage of human, animal, and environmental health. Among the most prominent is One Health, initially emerging from a collaboration between the World Health Organisation (WHO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2008 (Lainé, Morand, 2020, p. 2). Given the scale of current, global anthropogenic activities, including increasing globalization and changing land use, more pressing health risks arise, not only impacting humans, but equally important biodiversity and ecosystems as well (Degeling, Dawson, Gilbert, 2019, pp. 67, 68; Hill-Cawthorne, 2019, pp. 13, 14). Despite varying anthropocentric notions, One Health and other closely related frameworks, such as EcoHealth and Planetary Health, collectively aim to foreground the interdependencies of human, animal and environmental wellbeing (Degeling, Dawson, Gilbert, 2019, pp. 77, 78; Morand, Guégan, Laurans, 2020, p. 2).

Urban Healthscapes and Health in the City

The presented frameworks of health und the entanglements between human and more-than-human wellbeing become particularly tangible in an urban context as cities are often dense multispecies environments. In settings like this, questions of care, control, and coexistence rise and shape health interventions and more broadly, everyday healthscapes. Given that urban infrastructures, programs, and services tend to be anthropocentric-driven, the value of the environment and urban ecosystems is often minimized to the benefits they can offer to human health, so-called ecosystem services (Murray et al., 2022, p. 404; Pollastri et al., 2021, p. 1, 2). In this context, Pollastri et al. (2021) offer a new, rather ecology-centered approach that defines urban spaces, both landscape and architecture, as “mediated matter” (Pollastri et al., 2021, p. 1) and reevaluates multispecies coexistence in the city.

The need for more equal urban infrastructures that center the wellbeing of more-than-human entities as well becomes even more pressing when considering the effects of urban, anthropogenic activities on the environment. Artificial illumination and closely related to that light pollution and disruptions of circadian rhythms of certain species exemplify the challenges of managing coexistence and more-than-human health in an urban setting (Pollastri et al., 2021, p. 6).

Such challenges demand critical perspectives that acknowledge cities as shared habitats and recognize the agency of more-than-human entities. In Mainz, locations such as parks, animal shelters, or educational offers, foreground where and how health, care, and multispecies coexistence are negotiated.

Embedded in qualitative, explorative fieldwork, the city was explored through multiple walks, during which data was collected using a combination of qualitative techniques and further online research. Both familiar sites and newly discovered locations were included to capture a broad spectrum of urban, more-than-human

healthscapes. Those already familiar functioned as first anker points into the research field, while others were the result of the explorative search for fitting locations and materials. Observation formed an integral part of the fieldwork, with particular attention paid to signage, public infrastructures and organizations related to animal and environmental health. Additional material was collected to contextualize urban more-than-human health in Mainz and also give visibility to projects and initiatives that otherwise would have been easily overlooked. Physical flyers, posters, and brochures from public institutions, parks, animal welfare organizations and even an outdoor equipment store were gathered, alongside digital content from municipal websites and local initiatives.

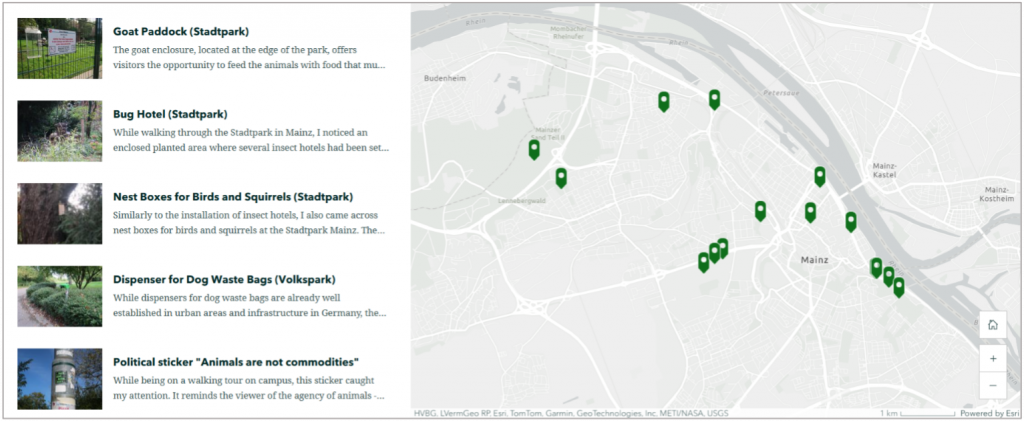

Utilizing the platform “storymaps”, provided by ArcGIS, the empirical data and findings are presented in the form of a cartographic blog, containing photographic essay elements. This output format not only visualizes the spatiality of the research topic but also makes the data accessible to a broader audience. Though such visualization, the project aims to raise awareness of more-than-human healthscapes in Mainz and highlight the links between humans, animals, the environment, and urban infrastructure in the context of collective well-being. Given the formal limitations and the qualitative nature of this study, the online blog presents only a number of insights into a much larger landscape of infrastructures, initiatives, and projects concerned with One Health, EcoHealth, and Planetary Health in Mainz, which also highlights the potential of the research objective for further investigation.

With regards to the chosen locations and storylines linked to more-than-human health geographies, a number of them exemplify how environmental education and inclusive project designs actively work towards raising awareness for multispecies health concerns and solidarity with more-than-human entities – important steps to mobilize the broader public for the promotion of positive change. Particularly, addressing the benefits of more-than-human wellbeing for human health can also enhance the value and agency people prescribe to those entities, recentering anthropocentric concerns and raising both moral and ethical questions. Lastly, this exploration of local health geographies was not only an act of academic research practice, but more importantly, encouraged me to reflect upon and reimagine urban spaces, how and for whom they are designed as well as how they can possibly foster an environment of wellbeing for all.

The online blog is accessible via the following link: https://arcg.is/0PaaPX0

References:

Andrews, G. J. (2018), Health geographies II: The posthuman turn, Progress in Human Geography, 43(6), pp. 1109-1119. DOI: 10.1177/0309132518805812.

Degeling, C., Dawson, A., and Gilbert, G. L. (2019), The ethics of One Health, in: Walton, M. (ed.), One Planet, One Health, Sydney University Press, pp. 65-84.

Hill-Cawthorne, G. A. (2019), One Health/EcoHealth/Planetary Health and their evolution, in: Walton, M. (ed.), One Planet, One Health, Sydney University Press, pp. 1-20.

Figure 3 Overview of blog entries

Lainé, N. and Morand, S. (2020), Linking humans, their animals, and the environment again: a decolonized and more-than-human approach to “One Health”, Parasite, 27, 55, pp. 1-10. DOI: 10.1051/parasite/2020055.

Lorimer, J. (2017), Parasites, ghosts and mutualists: a relational geography of microbes for global health, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42, pp. 544-558. DOI: 10.1111/tran.12189.

Morand, S., Guégan, J.-F., and Laurans, Y. (2020), From One Health to Ecohealth, mapping the incomplete integration of human, animal and environmental health, Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI), Issue brief 4/20.

Murray, M. H., Buckley, J., Byers, K. A., Fake, K., Lehrer, E. W., Magle, S. B., Stone, C., Tuten, H. and Schell, C. J. (2022), One Health for All: Advancing Human and Ecosystem Health in Cities by Integrating an Environmental Justice Lens, Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 53, pp. 403-426. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102220-031745.

Pollastri, S., Griffiths, R., Dunn, N., Cureton, P., Boyko, C., Blaney, A. and De Bezenac, E. (2021), More-Than-Human Future Cities: From the design of nature to designing for and through nature, 5th Media Architecture Biennale Conference (MAB ’20), Association for Computing Machinery (New York), pp. 23–30. DOI: 10.1145/3469410.3469413.

Rock, M. J., Degeling, C. and Blue, G. (2013), Toward stronger theory in critical public health: insights from debates surrounding posthumanism, manuscript version, pp. 1-14, available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/3823 (last accessed: September 20th 2025), later published in: Critical Public Health, 24(3), pp. 337-348. DOI: 10.1080/09581596.2013.827325.

Srinivasan, K. (2013), The biopolitics of animal being and welfare: Dog control and care in the UK and India, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(1), pp. 106-119. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475- 5661.2012.00501.x.

Whatmore, S. (2006), Materialist returns: practising cultural geography in and for a more-than-human world, Cultural Geographies, 13(4), pp. 600-609.