Lecture Series 2025 – Andreas Folkers: After sustainability. Reparations and resilience in times of planetary emergencies (Juli 2025)

For the summer term 2025 lecture series at the Institute of Geography, the cultural geography working group invited Andreas Folkers (IfS Frankfurt / Max Weber Centre for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies Erfurt). Andreas’ talk, titled “After Sustainability: Reparations and resilience in times of planetary emergencies”, posed questions around how to understand fossil modernity and to find ways to live with the products of fossil society, such as coal, oil, gas and their residues.

Andreas has previously worked on resilience, the government of emergencies and disaster preparedness, on time and temporalities as well as on biosocial relations and symbiotic collectives and climate politics and financial assets. His current project is concerned with what he terms fossil modernity. There, Andreas writes about three aspects of fossil materiality: resources (fossil fuels), residuals (CO2, plastic waste etc.) and reclamations of these residuals for current economic and political projects in two upcoming books, one in English with Zone Books, one in German with Suhrkamp.

In preparation for the lecture, students of the M.A. Human Geography: Globalisation, Media, and Culture discussed Andreas Folkers’ article Fossil modernity: The materiality of acceleration, slow violence, and ecological futures (2021, in Time & Society 30(2). Andreas proposes three modes of time to understand fossil modernity and the entanglements of time and matter, particularly fossil matter: dominant, residual, and emergent temporalities.

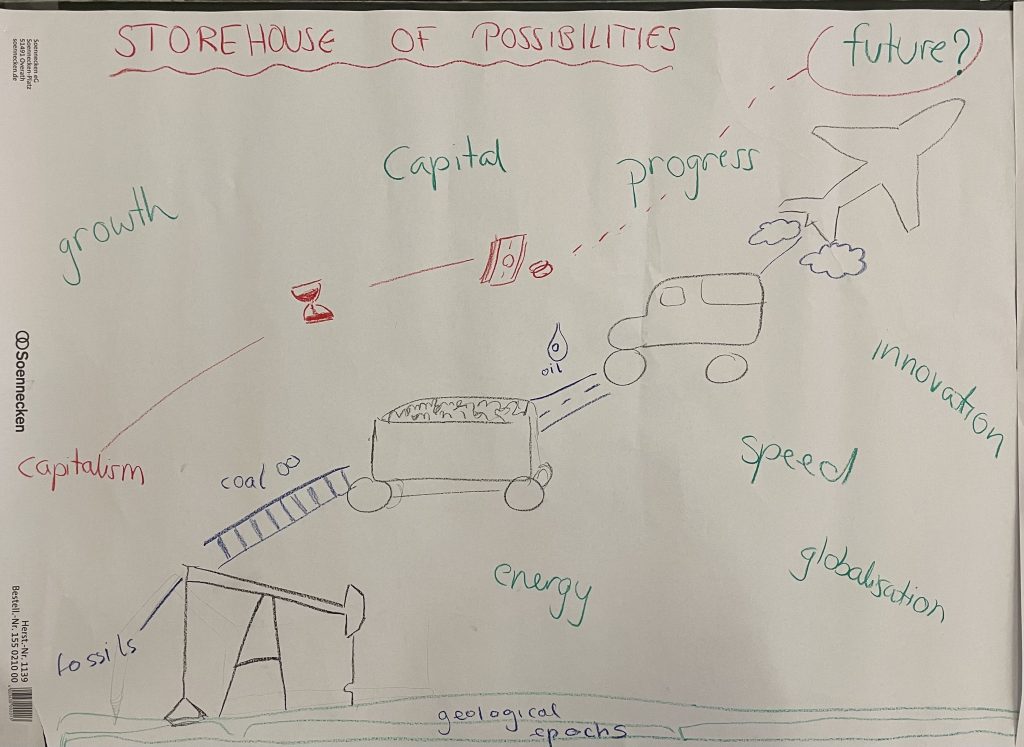

With dominant time, Andreas refers to a dominant conception of modernity as a storehouse of possibilities. Fossil resources, geologically and historically deep and slow, served as a reservoir for capitalist development, producing a new, accelerated and linear modern time. Capitalist production heavily relied on coal, and later oil and gas, for progress, innovation, and growth – making capital dependent on fossils and vulnerable to disruptions.

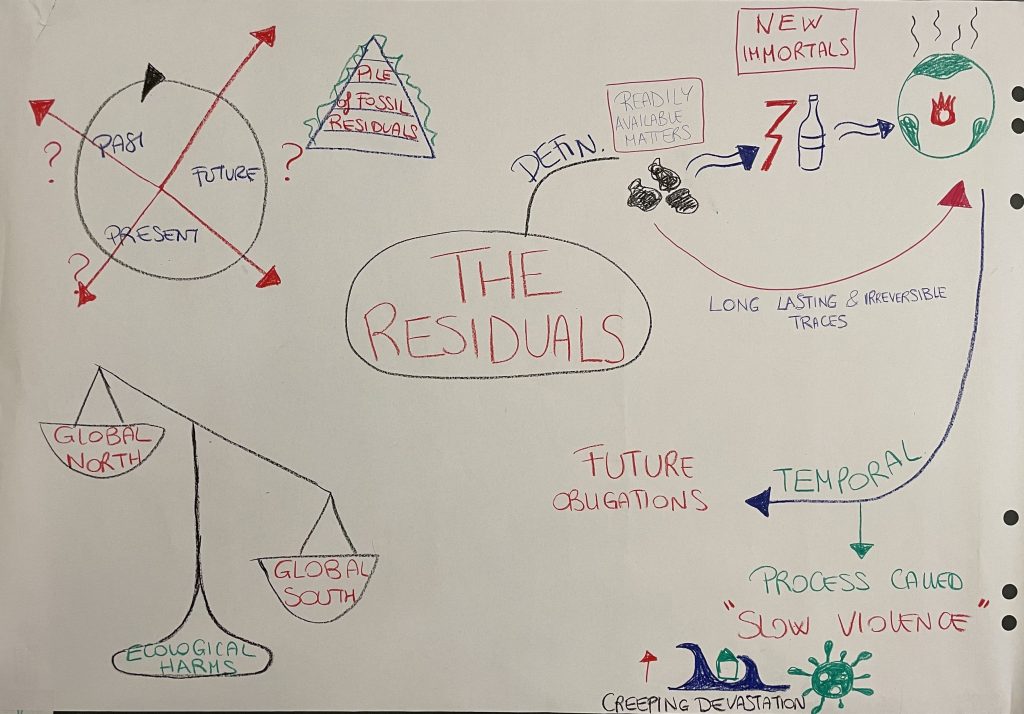

Under residual time, the residuals of fossil modernity are at the centre, especially the durability and slowness of waste products like CO2 and plastic – leaving long-lasting and irreversible traces on the Earth. These traces become visible over time in air, water as much as in human bodies, but are unequally spatialised, with marginalized regions and people affected by climate change much more. Fossil residuals thus create a new temporality, whereby the future is no longer a “storehouse of possibilities” but a “repository of liabilities” (p. 323) of ecological threats produced by the past, and time is no longer understood as linear.

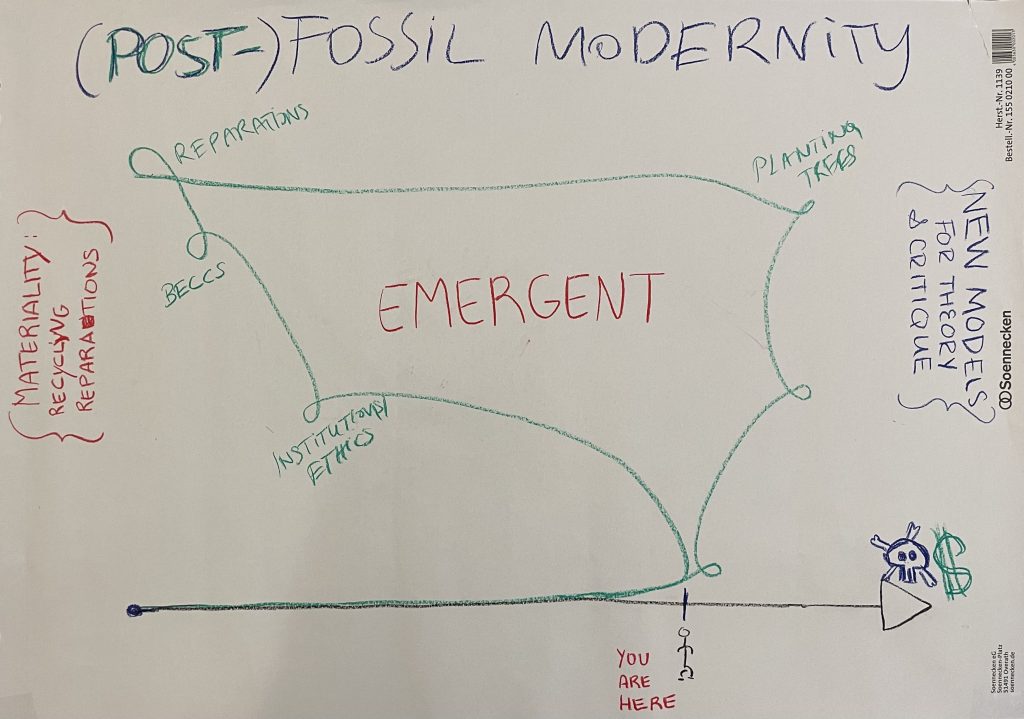

Lastly, emergent time poses the question of a possibility of post-fossil modernity: continuing as before, or focusing on different responses to fossil modernity, including recycling, reparation and redistributions (p. 235). These include longer-term bio-ecological developments such as plastic-eating microbes, the bioeconomy of alternative fuels as a technocratic-capitalist response to climate change but also demands regarding climate debt. Here, the residuals of fossil modernity contain tempo-material traces that serve as a sort of reservoir for claims against past, present and future inequalities.

In his talk, Andreas discussed fossil modernity in a similar way, albeit more focused on sustainability – or what comes after sustainability, as sustainability is in crisis: not just in terms of the scarcity of resources, but regarding fossil residuals, such as toxins and petrochemicals and resulting health problems, and the question of access to sustainable environments. Here, Andreas proposes reparation rather than sustainability and considering the Earth and atmosphere as an archive; carbon forensics could be used to calculate mitigation, for example; or residuals to make visible ocean currents and/or air movements. Resilience then needs to be considered less a way for disaster preparedness or a negative feedback loop but a view of what’s going on ‘behind the scenes’. This produces, then, a different understanding of nature as not just ‘out there’ but as entangled with fossil modernity. Here, then, are opportunities for a different future that focuses on recycling – in the form of natural measures of carbon capture and removal; regulation – of temperature, emissions, and also solar geoengineering; and resilience – in the way of creating a habitable earth by caring and repairing human’s earthly surroundings.