Starting fieldwork in India: First impressions and more

‘Fieldwork’ is something that my friends and colleagues in academia have always talked about enthusiastically, whether it’s related to experiencing new places and people for data collection, becoming familiar with different ways of life, observing the obvious but with a different lens, making new friends, tasting new food and whatnot. It’s like moving on to knowing the unknown. While I was preparing to leave for India for my fieldwork, I had two things on my mind: First, that fieldwork means going home to India to meet my family in Delhi after almost a year and second, that even though I will be in my home country I will then move on to my field site in Kerala which is not home at all, but a very different part of India to which I have not been before. Thus, I was curious and nervous at the same time. This was the first time that I was planning to do research all by myself where language could be an issue. Still I had selected Kerala as my empirical case study, as particularly the Alleppey district seemed to fit very well regarding my interest in collecting historical data and oral histories about living with floods and to crossread these with current flood management efforts, which are often mainly inspired by global policy recommendations.

While still in Mainz I already contacted people in state archives and libraries which paved the way for my initial data collection and also started some snowballing. After a weekend in Delhi with my family, I therefore travelled to Trivandrum (Image 1) , the capital city of Kerala, as my first stop for archival data collection. I was meeting my first informant here, who was helping me in finding resources. We both connected on our similar research interests and because I’m a native of Himachal Pradesh. Here, it matters a lot to people to know where you come from, where your native place is, and whether you are married. Even during introductions, when one of my informants introduces me to others in the local language, the first thing I heard him say was: ‘She is a native of Himachal and here for research.’ My name only came in the end. The moment people hear Himachal or Himalayas, they look at me with a surprisingly pleasant smile that gives me an assurance that they feel delighted to see me as I come from one of the northernmost states to the country’s southernmost region for my research. Most of the people I have met here so far have either visited the Himalayas or were willing to see them—those who have visited share their experience with great enthusiasm for how beautiful the mountains are. They ask curiously about my research objectives and how I perceive this place in terms of the weather, food, language and people. I observed that it’s a matter of pride for them that someone from that far has come to do her research in their region. They get a sense of responsibility for offering all sorts of help within their limits to ensure that I can do my work thoroughly and with ease. Furthermore, it surprises many people, especially young girls, that a woman is travelling in their state all by herself for her studies, and they feel motivated as most girls do not go far away from home alone.

Already during the first week I learned that fieldwork tests our patience a lot. The procedure to get permission to access the archives and to actually get access to the archival documents could be quite tedious and sometimes a bit frustrating. The first bump for me was when the officials at the archives department told me that the official process of getting the permission letter would take atleast one week, and the letter will only be delivered to my home address, i.e. Delhi. When I showed them that I had already emailed them two months back and they had not responded to me and with the support of my informant who works there, I was finally able to still pick up the permission letter in three days. This was then followed by a long and wearing process of going through the index, listing relevant documents, giving the list to the attendant and waiting for him to bring the files. But in the end, it was rewarding when I could see the data I wanted unfolding in front of me.

After that I was excited to finally travel to Alleppey district (images 2) to meet local communities. First, I met the district administration to introduce myself and interview them about their preparations for the upcoming monsoon season. My initial three weeks in the field had made me realise the importance of having a solid reference in moving forward with research. So, I asked the district authorities if they could help me in arranging accommodation in one of the villages. However, even after one week of followup, it turned out that it wasn’ t possible for them to find me a place to stay in the villages as nobody seemed to have a spare room that they would rent out to a stranger. The only places available were tourist resorts, but they were out of a researcher’s budget. For that reason, I opted to stay in town and decided to travel every day to the villages for my research.

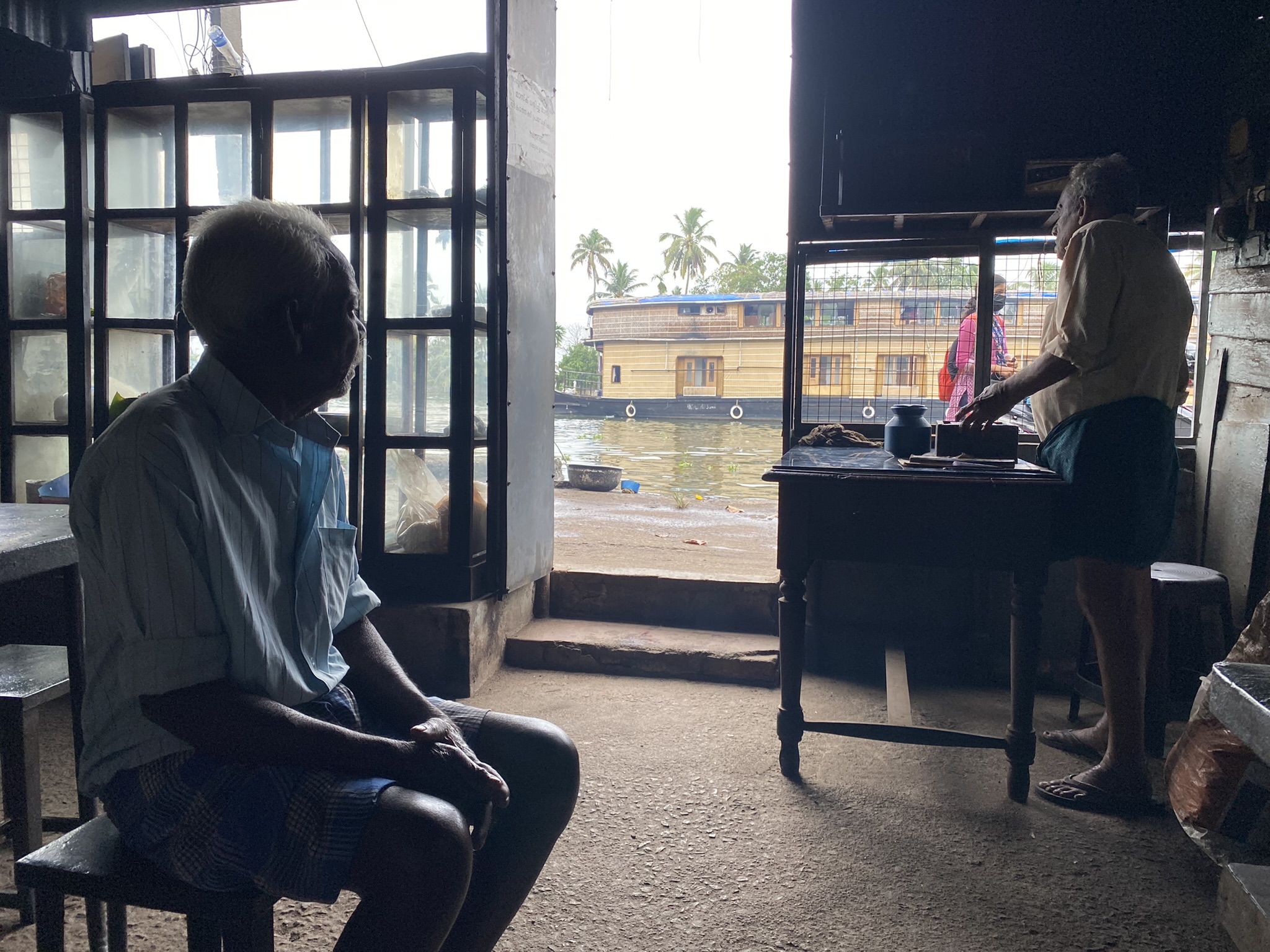

In the meantime, I have found some help from a local man who has close connections to some villages. I travel to these villages every day via local boats (image 3) and observe and interview people living there. Not every day turns out to be a success for various reasons. Somedays I can’t get anyone to talk to me, while I get 2-3 people to share their experiences on other days (image 4) . The key seems to be persistent and to find new ways to get people to talk to you. Some people offered to connect me with more informants, but later they ghosted me. That’s also part of the fieldwork experience.

But as I learn more about what matters to people here, what they care about and the stories they are willing to share, I’m optimistic that they will accept me, as they appear to accept the floods. And my origin in Himachal Pradesh may actually be helpful here, as it makes them explain their points of view in more detail since they know that I’m not familiar with their experiences.